Lately I’ve been reflecting on a recent read, On Trails, by Robert Moor. Looks like we’ve got a little impromptu series of posts going, you can read other thoughts from this book here and here.

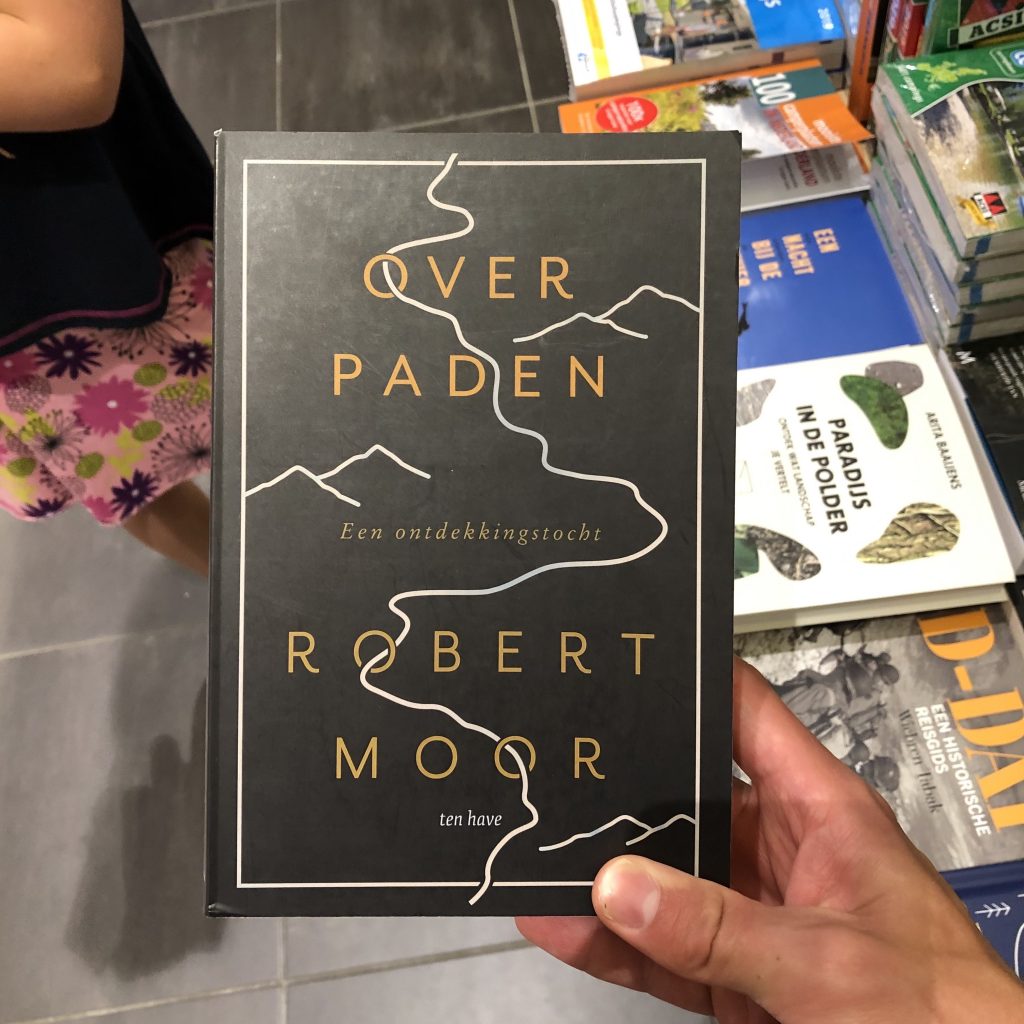

This book’s cover, even in its Dutch form, drew me in last summer, and this winter I finally had the chance to read it (in English). Moor offers a fascinating exploration of the formation and function of trails for us and other species. It reads like a good hike – meandering and reflective, but always pulling you forward through the landscape.

One of the ideas that stuck with me most was how ancient trail-walking cultures (as opposed to our road-driving culture) view the world. Moor relates some great metaphors for living a good life.

Smoothly, steadily, resiliently

Trail-walking cultures often grow to see the world in terms of trails. The Western Apache believe the goal of life is to walk “the trail of wisdom,” in pursuit of three attributes Basso translated as “smoothness of mind,” “resilience of mind,” and “steadiness of mind”—puzzling phrases if viewed independently, but perfectly clear when viewed within a metaphorical context of common walking (smoothly, steadily, resiliently) along a trail.

Smoothly, steadily, resiliently.

If you’ve read Christopher McDougall Born to Run, you’ll recall Caballo Blanco’s instructions about effective running in the trails of the Copper Canyon in Mexico:

Easy, light, smooth, fast.

Both of these metaphors portray a similar way of moving (or living) easily, in conversation with a landscape or trail.

Most religions, Moor points out, use the metaphor of a “path” or “way” when describing living rightly. It’s clear that trails have long been an important piece of human culture.

The Cree model for an ideal life is called the “Sweetgrass Trail,” while the Navajos’ ultimate good is a state of peace and balance they describe as “walking the beauty way.”

Osi and Tohi

The Cherokee also paint a vivid picture of living rightly and at peace. Not a static peace, but one that is active and moving through the world, like a stream. They call this “tohi”.

Among the Cherokee, the proper state of being for an individual is called osi, and the ideal state of all things is called tohi. According to Tom Belt, the words osi and tohi have no direct translation in English. Osi refers to the quality of a person who is poised on a single point of balance, centered, upright, and facing forwards. Tohi denotes something or everything, that is moving at its own speed, utterly at peace. An old man shuffling along the sidewalk can be tohi, as can a young warrior running at breakneck speed. Belt compared it to the flow of a stream, which runs fast one moment and slow the next, always moving exactly the pace that the land demands. When combined, an image of the ideal emerges: a person, upright, balanced, moving at a natural gait. Such a person is on what Cherokees call the Right Path, du yu ko dv i.

I love this image of a stream moving along its path. You might also think of music moving along at just the right pace, “in the pocket” as jazz musicians might say (see The Basie Way).

If you’ve ever seen Kilian Jornet running a descent, or a snowboarder cutting smooth lines through fresh powder, you know what tohi looks like in terms of moving over the land.

This winter our family picked up cross-country skiing. The first time I got onto my skis, the motion felt clunky and awkward. I was moving forward, but wasting a lot of energy simply trying to stay upright, far from osi. Meanwhile more experienced skiers moved smoothly and easily, making it look effortless. Tohi.

As we grow in wisdom on life’s path, maybe these metaphors convey our aspirations well. To move with more grace and ease. To move at our own speed, utterly at peace, as a stream flows along its path.