There’s a small green space near our house, in what has been called “the last piece of original bush” in our town. This is one of my favourite places to go for a morning run, or a walk with the family.

Care to join me on a little walk?

We wander out of town on a wide limestone path past the soccer park, down the winding trail northward through a stand of poplars. Round the bend, and towering above the surrounding brush stands an old tamarack tree.

This tree in particular has caught my attention over the years because, at first glance, it seems to be the only conifer tree in the whole 33-acre wood. It stands tall and straight, but with scraggly branches like a disheveled mess of hair all the way up its length. It’s stands off on its own, quietly asking for your attention from across the swampy clearing.

It seems almost out of place.

Remnants of a large stand

Tamaracks are different than most other needle-bearing trees in Manitoba. In fall the loose their needles, re-growing them each year like deciduous trees. The word tamarack is an Algonquian name for the Larix laricina species, means “wood used for snowshoes”.

Tamaracks, it seems, have long been known for their practical uses.

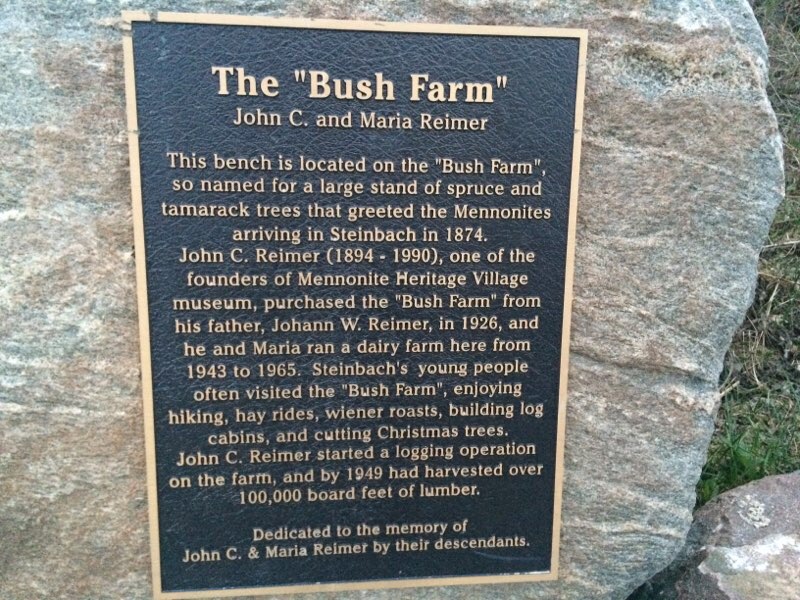

As we walk further down the path we find a plaque commemorating this place and its history (always read the plaque). The plaque honours the “Bush Farm”, a farm which once stood in this wood, and was so-named because of a “large stand of tamarack and spruce” that greeted the Mennonite settlers who moved into the area in the late 1800s.

Have we missed something? A “large stand” of tamarack and spruce? Granted, our lonely tamarack is not actually the last of its kind. On closer inspection, particularly in autumn when tamaracks glow with golden needles, you will find half a dozen tamaracks scattered across the wood, as well as a couple dozen spruce further from the path.

But this is no “large stand”. These Mennonite settlers must have found a different kind of bush when they arrived. (Of course, a sprawling parking lot that now occupies a large portion of this bush may have covered over some of our stand of spruce and tamarack.)

Regardless, it seems this area has changed a lot over the past century.

The plaque goes on to colour in the lines.

Lumber

John C Reimer, child of a Mennonite immigrant family, bought the Bush Farm from his father in 1926. The family ran a dairy farm in this location, and harvested lumber. In fact, by 1949 we’re told, 100,000 board feet of lumber had been harvested from the land.

I’m no expert in lumber, but judging by the size of spruce trees around here, this could mean 1500-2000 trees were harvested from this small forest to build the early foundations of the town that has now become home to 15,000 people.

Our old tamarack tree may not have looked so out of place one hundred years ago.

Armed with these details, more questions arise. Were the large spaces between poplars near the plaque once filled with conifers? How far did this bush extend beyond the boundaries established by farmland, roads, and the encroaching neighbourhoods?

I find myself curious to know what this place looked like in the 1940s, and before that.

This tree’s a “she”

In The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben talked about forests not as a collection of individual trees, but as a connected organism. (This concept of the connected forest is beautifully portrayed in Patagonia Films’ Treeline, which you should watch here.) Through his anthropomorphic lens, Wohlleben describes in familial terms, showing how larger trees who, because of their height, have greater access to the sun’s nutrients, help their saplings by sharing their nutrients with them. This lens has changed how I look at forests.

Each time I travel this path through Bush Farm, I acknowledge the old tamarack, imagining her as a matriarch of the forest. The wise elder of the wood who carries in her sinews memories of the past, and wisdom for future generations of life that flourishes around her.

Connected

In The Songs of Trees, David George Haskell explores trees in both forest and urban regions around the globe. His exploration expands on this idea of connectedness as he shows us how all life — trees, bacteria, bugs, birds, animals, humans — are all connected. We’re all part of and sustained by the complex systems that make up what we call “nature”.

Human lives and tree lives are made, always, from relationship.

– David George Haskell, The Songs of Trees

Our tamarack, anticipating the explosion of marsh marigolds around her base, the first new colours of spring, is a reminder of our connection. Her ancestors were felled to build the town that now borders the bush. This little bush points to the history of the place I now call home, and reminds me of my connection to the other life all around me. And it forms a home for countless birds, deer, foxes, and other creatures (hint: some of them are smelly).

Thanks for coming along. If you find yourself in the Bush Farm again, say hi to my old tamarack.

Update (June 16, 2019)

About a month ago I noticed that the plaque describing The Bush Farm had disappeared from its place on its rock.

I didn’t want to have to “show my work” in this post, but since the plaque is now at large (probably just in the shop for some polish?) I felt I should include it. Thanks to Erin Unger who serendipitously took a photo of the plaque shortly before it disappeared: