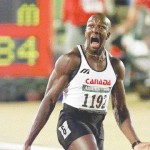

In the summer of 1996, Donevon Bailey became the fastest man in the world. Posting a record time of 9.84 seconds in the 100m sprint at the Olympics in Atlanta, the Canadian sprinter won gold and worldwide fame.

In the summer of 1996, Donevon Bailey became the fastest man in the world. Posting a record time of 9.84 seconds in the 100m sprint at the Olympics in Atlanta, the Canadian sprinter won gold and worldwide fame.

Watching at the age of 12, I remember every second of his race. And I remember the look on Donevon’s face when he realized what he’d accomplished. As he celebrated, my entire country rejoiced with him. What an unforgettable moment!

Well, Donevon may have become the fastest man in the world in 1996, but someone else took the title in 1997.

And that someone… was me.

Growing up, I was always into sports. But I was one of those kids who played “just for fun”. (That’s what parents tell kids who never win anything). The first sports award I ever won was a consolation bronze medal for coming in sixth place (out of six teams) in a baseball tournament. But we didn’t seem to care that we got last place, we had real medals around our necks!

As a “just for fun” athlete, you can imagine my excitement when, at the age of 13, I qualified to compete in the annual track and field day! I had qualified in a couple of events, but the one I had my eye on was the 100m sprint. Having witnessed Donevon’s Olympic victory and instant fame, I knew that the 100m was the event to win. Win the 100m and fame and fortune waited for you at the finish line, not to mention the coveted title of “the fastest man in the world!”

If I could win the 100m sprint, all my past athletic failures would be forgotten as my name was etched in the record books. This was my chance of a lifetime!

On track and field day, the weather was perfect. Buses from around the school division converged at our oval track for the day’s festivities.

Around noon, a cluster of hopeful 13-year-old boys gathered at the starting line for the 100m sprint.

And I was nervous.

Next to me in the lineup was none other than Ryan. Ryan towered a foot taller than me and was a track and field star. He was competing in just about every event that day. He had real running shoes, and those things on this arms that most 13-year-old boys only dream abot… that’s right, he had biceps!

To make matters worse, next to Biceps was none other than Ian. Ian was on his way to a career in professional hockey, but even at the young age of 13 – heck, even at the age of six – that kid was a professional athlete. (He’s the one who made gym class floor hockey so frustrating…).

Next to Biceps and Blades… was me. Admittedly as a teenager I spent more time doing homework and practicing scales on the piano than firing slapshots or… doing whatever people with biceps do.

It was David against not one, but two Goliaths.

But maybe, just maybe, if I had enough determination and passion, I might have a chance to beat them both and claim elite status at last.

As the gun went off you could hear 15 pairs of eager feet speeding down the track.

In a matter of seconds I’d pulled away from the pack, along with Blades and Biceps. I had a chance! Arms pumping, legs churning, I slowly inched ahead of Blades. Levelling my gaze on the finished line, I strained ahead with every bit of strength I could muster.

Within steps of the finish, I edged past Biceps, and crossed the line first!

I had done it! I was the champion!

Flowers fell from the heavens. I could hear a choir singing my praises. This was my moment! I couldn’t believe it!

Biceps came over and congratulated me. Blades was evidently not too happy, but that’s just how I wanted it…

I hadn’t broken Donevon Bailey’s world record, but in my 13-year-old world I was a legend!

… for about 2 hours.

Unfortunately, the other event I’d qualified to compete in was the 400m. To be clear, 400 metres is four times further than 100 metres. It’s one full lap of the track.

As I sauntered to the starting line, full of swagger and confidence, I surveyed the competition. This time there was no Blades, no Biceps. It was just me and a bunch of kids who obviously didn’t have the same championship-winning drive as I did.

As it turns out, that didn’t seem to matter.

Though I tried to sprint to an early lead, it wasn’t long before I was falling behind the pack. With my championship-winning legs protesting, lungs gasping for breath, I quickly realized that this wasn’t my race. Deflated, I crawled across the finish line in a solid last place.

I learned a couple things that day.

First, winning one race doesn’t mean you can win every race. And second 100m multiplied by 4 is… a really really long way.

Fortunately, time has a way of healing scars. All that remains is the sweet memory of victory.

To this day, whenever my father needs to boost his ego or one-up a buddy, he’ll tell of the time when his son beat an NHLer in a sprint.

Personally, I’m still waiting for Donevon Bailey to return my voicemails: “Don, it’s Brent. You may have been the fastest man in ’96, but I was the fastest man in ’97. It’s time to settle the score.”