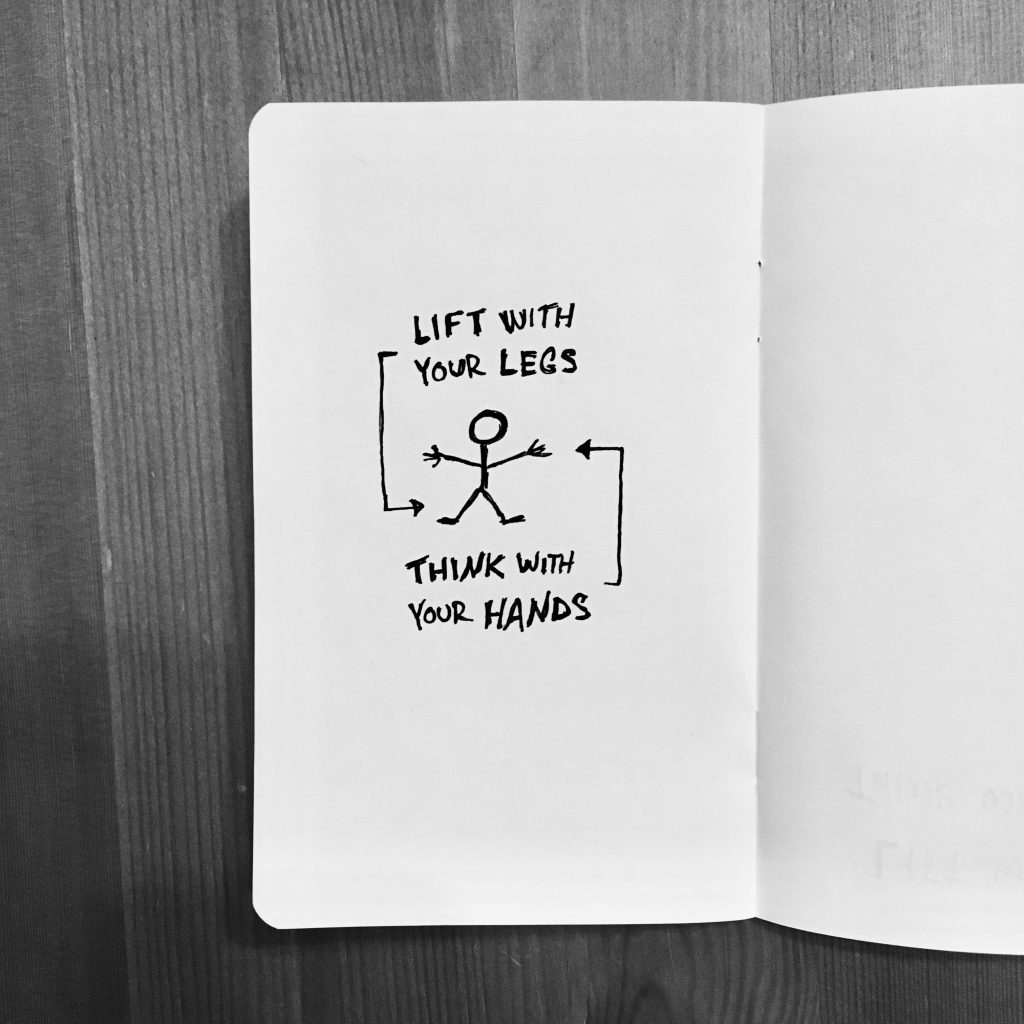

We all learned years ago that lifting heavy objects was a job for our entire body, not just our hands. Turns out that thinking is the same. It’s not just a job for our brains, we need our whole body to think.

“Mrs. Lynne, Gillian isn’t sick; she’s a dancer.”

In his landmark TED talk (and later his book, The Element), Sir Ken Robinson tells the story of Gillian Lynne.

In school, Gillian wasn’t very bright. In fact, her school was quite concerned about her. She had difficulty paying attention, was always fidgeting, and disrupted the class. They thought she might have some kind of learning disorder.

Her concerned parents eventually took her to a specialist to figure out what was wrong with Gillian.

In the end, the doctor went and sat next to Gillian, and said, “I’ve listened to all these things your mother’s told me, I need to speak to her privately. Wait here. We’ll be back; we won’t be very long,” and they went and left her.

But as they went out of the room, he turned on the radio that was sitting on his desk. And when they got out, he said to her mother, “Just stand and watch her.” And the minute they left the room, she was on her feet, moving to the music. And they watched for a few minutes and he turned to her mother and said, “Mrs. Lynne, Gillian isn’t sick; she’s a dancer. Take her to a dance school.”

In dance school, Gillian found a tribe of people who, just like her, “had to move to think”. Having discovered her passion for dancing, she went on to become a dancer in the London Royal Ballet, and the famed choreographer behind such productions as Cats and Phantom of the Opera.

Not bad, for someone who couldn’t sit still in school.

Moving to think

I’ve been thinking about “full body thinking” in a couple contexts.

First, as a parent, am I helping my children develop into humans who make the most of their entire bodies, not just their brains? Schools have changed a lot since Mrs. Lynne disrupted her class in the 1930s, but we still often prioritize the thinking that happens in our heads above the other kinds of intelligence. As Robinson went on to exhort in his TED talk, “Our task is to educate [our children’s] whole being.”

And as a grownup, am I making the most of my whole body’s ability to move and think? In today’s “knowledge economy”, many of us spend all day sitting in front of a computer to do our work. Machines do much of our heavy-lifting at home and work. If you have a desk job, it can be hard to keep your whole body involved. Once your legs have to carried your brain and fingertips to said desk, then their job is largely done for the day! But by leaving thinking to your brain alone, are you really at your best?

Like Lynne, I often find that I have to move to think. My mind feels its clearest after a good run, which is part of why a morning run has become such an essential part of my daily routine. I also take frequent breaks throughout my day to re-engage my legs. A simple change of scenery can bring clarity to the toughest problem, jog memory, and reduce stress.

I’ve also started carrying a notebook around everywhere I go. By turning to pen-and-paper rather than my phones to jot down notes, I engage my fingers in a different way, which helps me remember what I’ve written, and draws on my fingers’ intelligence in working out problems and drawing connections.

How do you get your mental wheels turning? With your hands, your feet, your voice? How do you engage your whole body in your routine?

Because sometimes your brain can’t do all the work alone; you need your whole body to think.

—

Related:

- Read Austin Kleon’s blog post on this subject.

- Here’s Sir Ken Robinson’s full TED talk on education and creativity: